This is a guest post by Andrea Reisenauer

Between Brexit, the recent US election, and important upcoming elections in France, Germany, and Iran, 2016 and 2017 will mark significant years in world politics. From immigration policy to legislative representation, language has taken to the stage alongside many modern debates.

Today, we'll travel to places where a foreign or minority-spoken language means so much more than just grammar and vocabulary. We'll take a look at some of the politics behind language promotion in Spain, presidential multilingualism in the US, the birth of new languages in Eastern Europe and national attitudes towards languages in several countries around the world.

1. Language and the Rise of Nationalism

Throughout history, languages have often been used politically to promote social cohesion or a sense of national pride in large, culturally diverse countries.

China is a great example of this.

After the Chinese Xinhai revolution in 1911, Chinese nationalists known as the Kuomintang founded the Republic of China. With it came the responsibility to govern and manage a multilingual country as diverse as its over 50 recognized minority languages. In order to promote a sense of national unity and to improve communications within the nation, the new government decided to designate a national language. Thus, the Mandarin Beijing dialect was chosen as the national language and remains so to this day.

20th-century China is just one of countless examples of countries that have promoted a national language to improve communication and foster feelings of nationalism and togetherness.

In a controversial announcement in 2014, one German political party advocated for immigrants to be required to speak German--even in their own homes. While this may be a very extreme example, this Bavarian party leader's call represented a growing trend towards fear of losing widely spoken national languages due to an increase in immigration.

Today, a similar movement can even be found in the United States. The modern English-only movement was born in 1983 and seeks to pass a law declaring English as the sole official language of the United States. On a national scale, the law would both attempt to expand opportunities for speakers of foreign languages to learn English and suppress foreign language growth and bilingual education programs.

In what is now a country with the second highest number of Spanish speakers in the world, the English Only Movement is a symbol of the call for an official language to promote nationalism.

2. Speak American, Mr. President

Despite the large number of languages present in the United States (at least 350), to be more precise), there have only a small handful of bilingual US presidents. In the past 116 years, only three could speak a foreign language fluently: Theodore and Franklin Roosevelt (French and German) and Bill Clinton (German). Only four had an elementary command of foreign languages: Herbert Hoover (Latin and Chinese), Jimmy Carter (Spanish), George W. Bush (Spanish), and Barack Obama (Indonesian).

But how is it that a president of such an internationally powerful and diverse country is allowed to only speak one language?

In reality, speaking a foreign language is sometimes actually considered a negative practice for presidential candidates since it may contribute to anti-American ideology. In 2004, John Kerry was insulted by George W. Bush for being a fluent Francophile who "looks French," and Barack Obama was criticized in 2008 for his upbringing in Indonesia.

Speaking only English is often a way for presidents to show their national pride, and many voters seem to display a hidden fear that a multilingual candidate is not "genuinely American," according to political scientist Dr. Larry Sabato. Strategically speaking, having to rely on a translator may also allow US politicians more time to think, according to another historian, but this strategy may easily be argued. When it comes to foreign languages in the US, it appears that the fewer languages the better for a presidential candidate.

3. Language and the Fight for Recognition

Just as a majority language may be promoted to incorporate minorities and foster nationalism, a minority language may also be promoted to give a voice to sub-nationalism and foster recognition.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the sub-nationalist Basque and Catalan communities in Spain. Both Basque and Catalan nationals have maintained linguistic, cultural, and economic differences with the rest of Spain for centuries and seek independence from Spain to this day.

In Basque country, we find the unique, pre-Indo-European Basque language that was publicly frowned upon under dictator Francisco Franco. After Basque achieved the status of an official language in 1978, the language became an increasing means of representing a sub-nationalistic voice calling for the region's independence from the rest of Spain.

The Catalan language shares a similar history. After historical attempts to suppress the Catalan language and culture and a surge in immigration from Southern Spain, the Catalan language lost prestige and was increasingly losing speakers. After the death of Franco in 1975, the 1978 constitution recognized Catalonia's right to have another official language and Catalan is now required in Catalonian schools. There is more drive than ever to preserve a language and culture that was once forbidden by Franco, and a strong sense of Catalan nationalism and drive towards independence from Spain remains. Now, Catalan is the ninth spoken language in Europe in terms of speakers, proving that banning a language may be an effective way to preserve it.

English in the UK has also been challenged by minority languages looking for a cultural and political voice. In Northern Ireland, both the Gaelic Irish language and the West Germanic Ulster Scots dialects are considered a valuable part of the country's cultural wealth. They are promoted by the Irish Institute and Ulster-Scots Agency respectively in an effort to preserve and foster regional identity. Similar efforts have taken place in Scotland, where Scottish Gaelic is fighting for its status as an official language of Scotland to gain equal respect to English.

If you're looking for a similar linguistic sub-nationalism a little bit closer to the US, look no further than Quebec, our Francophile neighbors to the north. As the second most populated province in Canada, Quebec is dominated by the French language. Despite being surrounding by English-speaking provinces, Quebec's sole provincial official language is French thanks to Bill 101 introduced in 1977. This bill was one of many regional steps taken to gain the province's independence and preserve its French identity. While particularly strong in the late 1900's, feelings of national pride and the desire to preserve and promote the French language remain in Quebec today.

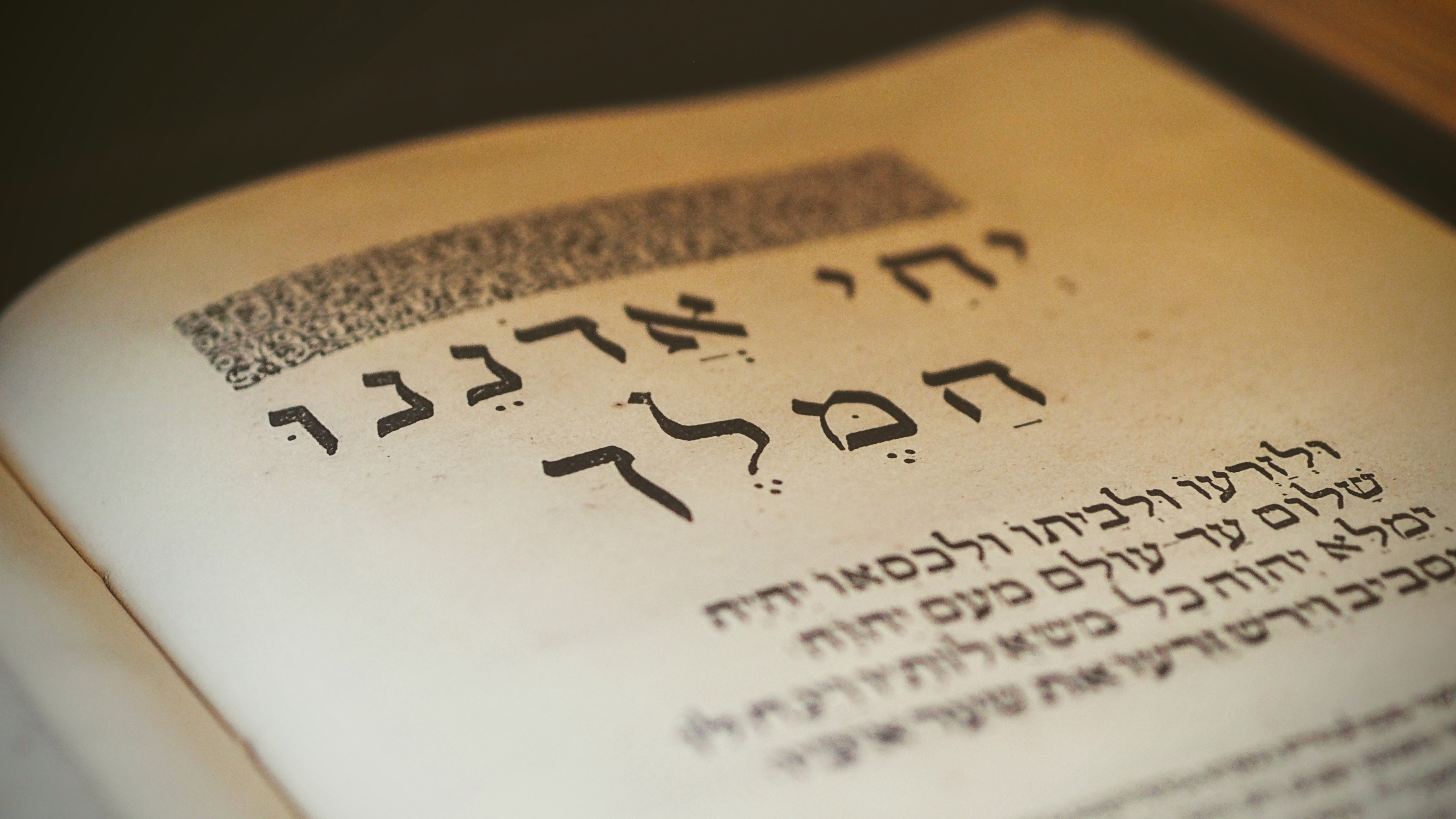

4. The Rebirth of Hebrew

Throughout history, language has been a political tool to not only silence the voice of the minority, but also to allow it to be heard. From the Catalans and Scots to the Quebecois to the Native American nations to the Maori tribes of New Zealand and everyone in between, minority languages have been used to foster sub-nationalism and give a voice to those who were once silenced.

But what if the minority language you hope to promote is no longer in use?

Look no further than the case of Hebrew, a formerly extinct language whose revitalization began with a group of Israelis at the end of the 19th century when they decided to begin exclusively speaking Hebrew. Hebrew had been extinct for thousands of years and was only used as a sacred liturgical language. Within a few decades, however, the language was increasingly more spoken and transformed into the lingua franca, or common spoken and written language, of Israel and the Jewish part of Palestine. It is now recognized as an official and literary language in Israel since the British Mandate of Palestine and has gone hand-in-hand with Jewish modernization and political movements. Hebrew was, essentially, completely revitalized.

The case of Hebrew is a very unique one and it has served as a model for other language revival attempts. The formerly at-risk or extinct languages of Irish, Welsh, Hawaiian, Cherokee and Navajo all underwent similar revitalization processes, and the globalization of the English language has led to an increasing trend in attempts to revitalize at-risk languages.

5. It's All About the Border

While many regional languages are being revived to foster feelings of nationalism and back independence campaigns, other languages are being adopted or formed due to a shift in political borders or cultural differences.

Hindi and Urdu are a great example of this. Other than a different form of writing (Urdu uses the Perso-Arabic script called Nastaliq while Hindi uses the Devanagari script), Hindi and Urdu are essentially the same spoken language. However, they are considered different languages simply because they are spoken in different countries. While Urdu is associated with Muslim Pakistan, Hindi is associated with the Hindu country of India. There is an ongoing dispute over whether or not the two should be considered a single language and what that would mean politically and culturally for the Hindi and Urdu people.

An even more extreme example of this can be seen with the Serbian, Croatian, and Bosnian languages. All of these languages were once one and the same (Serbo-Croation) in the former Yogoslavia. They were simply considered different local dialects and writing systems. Just within a few years after the breakup of Yogoslavia, however, three new languages emerged even though their systems hadn't changed at all. Essentially, a change in borders led to the creation of and promotion of new languages.

As many linguists will say, "a language is a dialect with an army and a navy." It's All Connected From enforcing a widely spoken language to reviving a minority language or forming a new language with the birth of a new country, there's no doubt that language and politics have gone hand-in-hand throughout history.

Political conditions have a strong influence over a community's perception of a language and the role a language plays in society. No matter what your political views are, there's no doubt that both language and politics have gone together to help shape history and that they will continue to do so.

Do you know any other interesting cases of language and politics going hand-in-hand? Feel free to share in the comments below!