Ancient Greek texts, Egyptian Hieroglyphics, Old Norse Viking ruins... Who isn't fascinated by the languages of the past? Whether you're hoping to go on an Indiana-Jones-style adventure, read ancient sacred texts, learn from the past or simply hope to learn modern languages more easily, learning a dead language may be your answer.

Before talking about some of the benefits of learning dead languages, let's take a look at what a dead language is, whether or not it can be revitalized, and some well known dead languages.

What is a dead language?

A dead language is a language that no longer has any native speakers, although it may still be studied by a few or used in certain contexts. If there are only a few remaining elderly speakers of a language and it is no longer used for communication, then that language is effectively considered dead even before its last native speaker has passed away. The death of a language is rarely a sudden event, but usually takes place gradually as a language is marginalized or slowly replaced by other languages. Some of the most well known dead languages include Latin, Sanskrit, Old English, Aramaic, Ancient Greek, Old Norse, Coptic, Iberian, Etruscan and Proto-Indo-European, just to name a few.

Dead languages are often confused with extinct languages, or languages that are no longer in current use and don't have any active speakers. While some scholars have tried to draw a line between the two, in reality, dead languages and extinct languages have undergone more or less the same phenomenon: they have lost native speakers and are no longer commonly used.

Due to increasing globalization, thousands of languages are becoming extinct or are at current risk of extinction. The world's linguistic diversity is steadily declining as major world languages (such as English) take over and languages with less speakers begin to die out, or lose native speakers.

Almost a quarter of the world's languages have less than a thousand remaining speakers, and many linguists estimate that at least 3,000 languages are guaranteed to become extinct within the next century.

Can a dead language be brought back to life?

The death of a language is the death of culture and a unique way of seeing the world. For language lovers, that's even more tragic than the extinction of a species. There has to be something we can do to help keep the world's languages alive, right?

Fortunately, a dead language can be brought back to life, or revitalized, by actively studying and speaking that language and passing it down to the next generation. As soon as children begin learning a language as their native language, that language has been revitalized and is considered a living language.

The best example of a dead language being revitalized is the case of Hebrew, starting with a group of Israelis deciding to begin exclusively speaking the language at the end of the 19th century. Hebrew had been extinct for thousands of years and only used as a sacred liturgical language. Within a few decades, however, the language had become more and more spoken and was transformed into the lingua franca, or common spoken and written language, of Israel and the Jewish part of Palestine. It is now recognized as an official and literary language in Israel since the British Mandate of Palestine and has gone hand-in-hand with Jewish modernization and political movements. Hebrew was, essentially, completely revitalized.

The case of Hebrew is a very unique one, and it has served as a model for other language revival attempts. The formerly at-risk or extinct languages of Irish, Welsh, Hawaiian, Cherokee and Navajo all underwent similar revitalization processes, and the globalization of the English language has led to an increasing trend in attempts to revitalize at-risk languages.

Why should I learn a dead language?

If the idea of helping to bring a language back to life isn't reason enough to learn a dead language, learning a dead language may have some very interesting and unexpected benefits.

First of all, learning a dead language helps open the door to a past and history that many modern languages can't offer. It teaches a cultural sensitivity and historical understanding that can, essentially, help us to effectively learn from the past. It gives us interdisciplinary access to the thoughts and ideas of human beings hundreds or thousands of years ago and allows us to hear their voices and learn from their wisdom. It is, quite frankly, just plain fascinating.

Much like learning a modern language, learning a dead language also has many of the cognitive benefits that language learning offers us, from an improved memory and decision making skills to a decreased risk of dementia.

Finally, learning a dead language can actually help you to learn many modern languages. In order to better understand this, let's take a look at language families.

A language family is a group of languages that can be proven to be genetically related to one another (and by genetically, I mean linguistically, of course!). The most well-known languages come from the Proto-Indo-European family, which later expanded and grew to evolve into the Anatolian, Celtic, Romance, Germanic, Baltic, Slavonic, Iranian, Indic, and Green language families. This can be best visualized in the shape of a tree, or the world language tree:

Of course, this tree only represents the main language families, and not all of the world languages. There are over 7,000 languages in the world today, the majority of which can be sorted into the groups found on this tree.

Essentially, by learning an older (and perhaps dead) language farther down the "trunk" of the world language tree, you can learn the roots of many modern languages and therefore make learning one of these languages easier.

Take the case of a Sanskrit teacher, a friend of a friend of mine, as an example. He teaches a dead language that was the root of many Indic languages, and claims that knowing Sanskrit makes picking up other Indic languages much easier. As a result, he speaks around 20 languages, 15 of which had Sanskrit roots. Of course, he also has a natural knack for language learning, but knowing a dead language was his door to many modern languages that had evolved from Sanskrit.

The same, however, is true of learning a modern language: learning a modern language can also help you to understand and learn a dead language. If you learn Spanish, Italian or French, for example, understanding and learning Latin and Latin texts is significantly easier (trust me, it's true!).

From discovering ancient worlds through texts to learning modern language, learning a dead language isn't as impractical as many paint it to be. The Best Dead Languages to Learn Now that we've seen some of the benefits of learning a dead language, let's take a look at five of the best (in this case: most interesting and practical) dead languages to learn, when and where they were spoken, which texts they can help you to read, and which modern languages they may help you to learn.

1. Latin

Latin is by far one of the most studied dead languages due to its popularity in the Western world. It's also one of the most familiar thanks to its widespread use in schools and universities, the Christian church, and legal and political affairs. We also already use the Latin alphabet, which makes learning Latin much easier. After the Norman conquest of English in 1066 AD, French (and therefore Latin) began to merge with the formerly Germanic English, leaving us with a language that has nearly one third of its roots in Latin.

- When: from approximately 800 BC to the Renaissance (in both its classical and medieval form)

- Where: the former Roman Empire, early Modern Europe, and the Vatican City

- Texts and Writers: Augustine, Cato, Catullus, Cicero, Julius Caesar, Marcus Aurelius, Ovid, Seneca, Thomas Aquinas, and Vergil, among others

- Languages it may help you learn: Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, French, Romanian, English, Catalan, Galician, Romansh, Venetian, Corsican, Neapolitan-Sicilian, and Sardinian, among others

2. Sanskrit

Ancient Sanskrit is the Latin of the Eastern world and has a similar status. Its grammar rules were established around 400 BC and it became a scholarly and ecclesiastical lingua franca of the Indian subcontinent for over three millennia. The language itself boasts a large, 49-letter alphabet, and the western number system and many languages around the world evolved directly or indirectly from Sanskrit.

- When: from approximately 1500 BC to modern times (as a liturgical language)

- Where: India and southeast Asia

- Texts and Writers: The Vedas, a large body of sacred texts that provided the foundation for Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism

- Languages it may help you learn: almost all Indo-Aryan languages east of Iran, including Hindi, Urdu, Punjabi, Gujarati, Nepali, Marathi, Bengali, Rajasthani, Assamese, Sinhalese, Maldivian, Romany, among many others

3. Old English and Middle English

Also commonly referred to as Anglo-Saxon, Old English is one of the foundations of Modern English. It was the language of the Germanic settlers of England for nearly seven centuries, and has three dialects: West Saxon, Kentish, and Anglian.

- When: approximately 500-1066 AD

- Where: England and southern and eastern Scotland

- Texts and Writers: Beowulf, Caedmon's poems, Cynewulf, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the writings of King Alfred

- Languages it may help you learn: English, German, Dutch, Old Dutch, Old Norse, Icelandic, West-Flemish, and Frisian, among others

4. Ancient Greek

Often considered the most important language in the intellectual life of western civilization, many of the modern English words used to refer to scientific fields come from Ancient (or Classical) Greek (psychology, philology, theology, philosophy, etc.). While it does use an older and more foreign alphabet, learning Ancient Greek can allow you to read many ancient intellectual texts.

- When: the 9th century BC to the 4th century BC

- Where: the Greek peninsula

- Texts and Writers: Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Homer (in the Ionic dialect), Herodotus, Euripides, Aristophanes, the New Testament (written in the Koine dialect)

- Languages it may help you learn: English, modern Greek, Yevanic, and Cypriot, Crimean, Romano and Italiot Greek

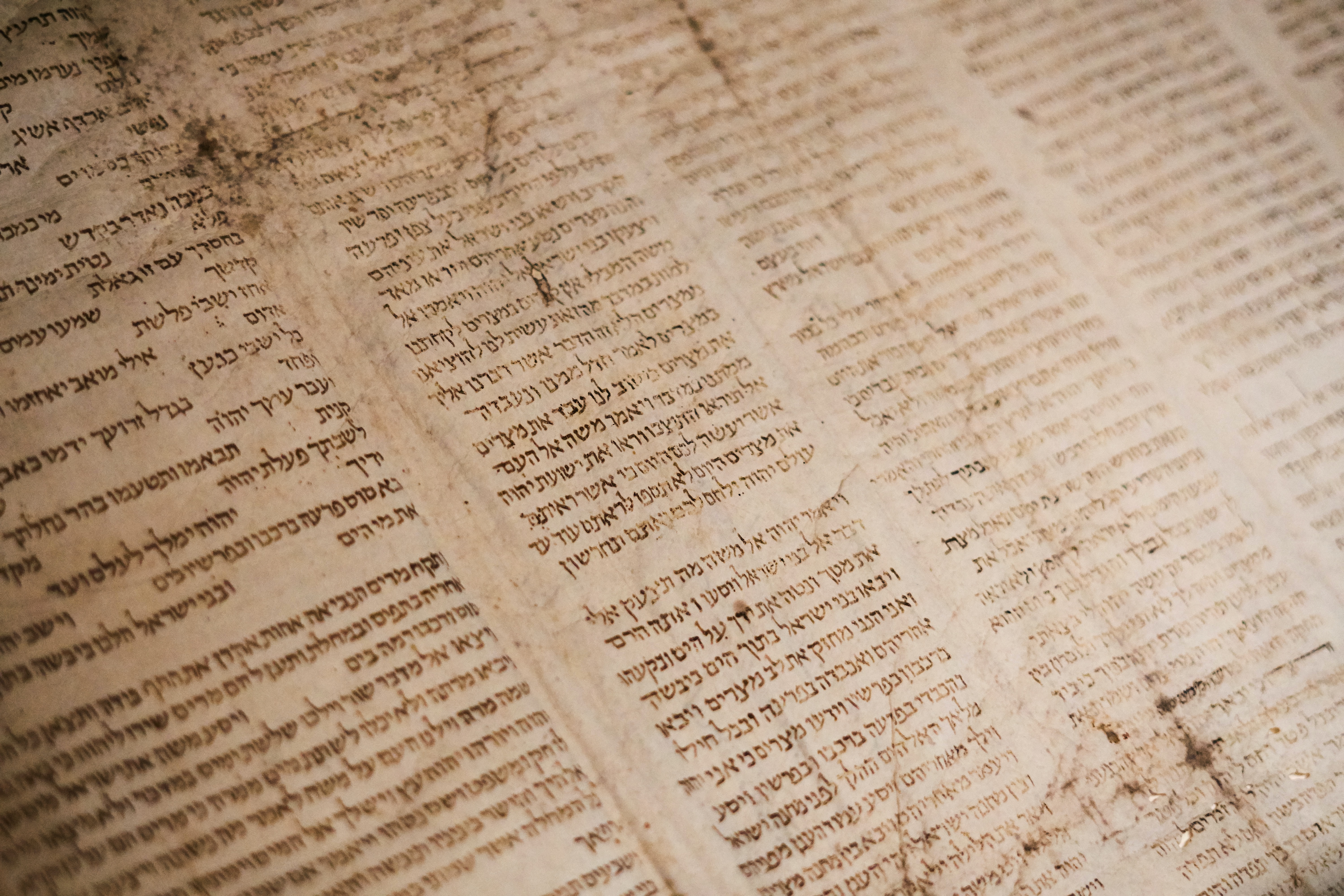

5. Biblical Hebrew

Biblical Hebrew is the archaic form of modern Hebrew used to write the Old Testament of the Bible. It's a very popular language for Jewish and Christian followers to study because it allows for the opportunity to read the Old Testament of the Bible in its original language. While it is very similar to Modern Hebrew, the style, grammar, and vocabulary of Biblical Hebrew makes it much more difficult to learn.

- When: approximately between the 10th century BC and 70 AD

- Where: ancient Israel

- Texts and Writers: The Old Testament or Hebrew Bible, Jewish liturgy

- Languages it may help you learn: Arabic, Amharic, modern Hebrew, Tigrinya, among other Semitic languages

Of course, these aren't all of the dead languages that may be useful to learn. From Akkadian (the language of ancient Mesopotamia) to Old Norse (the language of the Vikings) to Latin and everything in between, dead languages are our window into the past and can provide us with a variety of unexpected benefits.

Whether you're looking to solve history's mysteries, uncover the truth behind ancient texts or simply would like to make learning a modern language a little bit easier, dead languages are your answer. Bonam Fortunam!

This is a guest post by Andrea Reisenauer. Please share this article!